Фундаментальная Роль Интерфейсов в Языках Программировния

В этом тексте я попытаюсь объяснить, для чего существуют интерфейсы. Делаю это я, как обычно, прежде всего, для себя и для тех, кто обращается ко мне с подобными вопросами. Через аналогии я поясню, почему они необходимы и как могут быть полезны. Кроме того, я приведу несколько примеров, чтобы продемонстрировать их преимущества и возможные трудности.

Аналогии

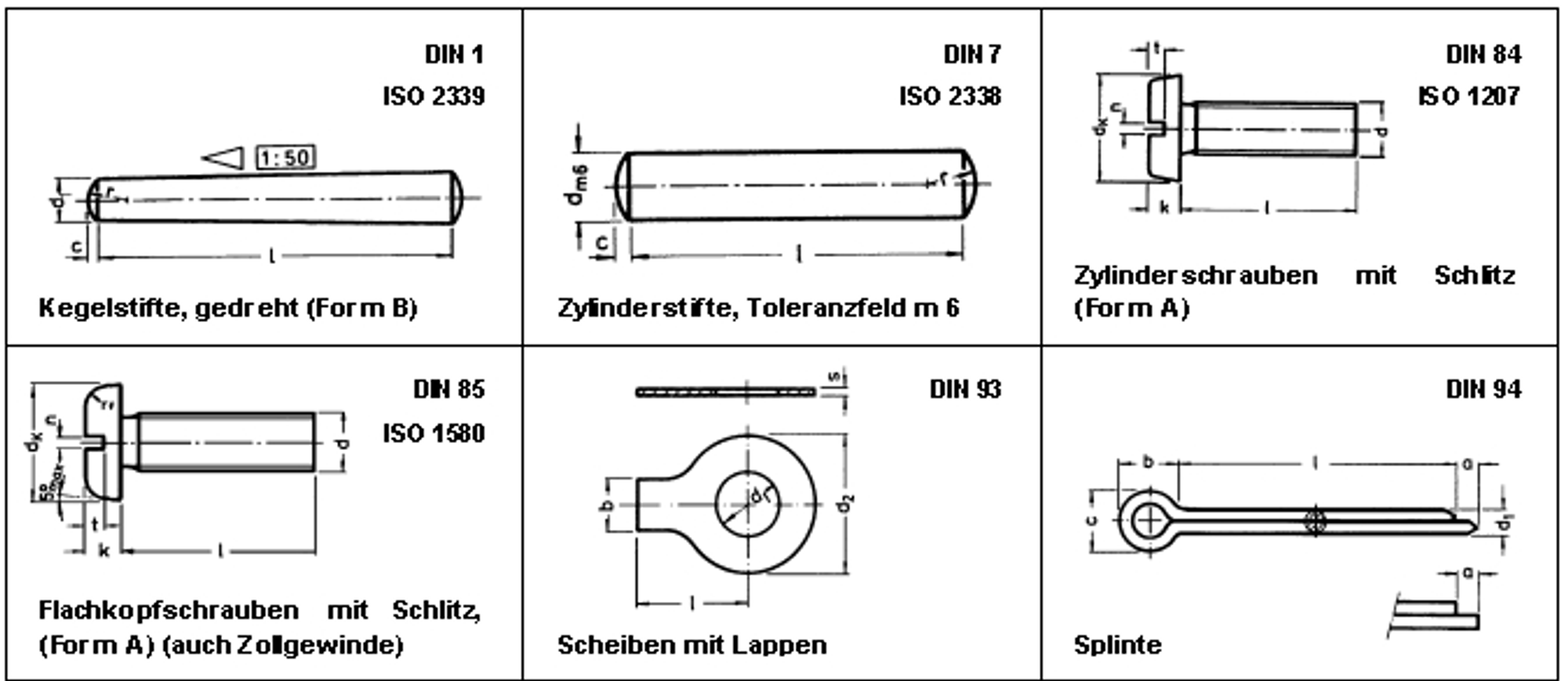

Разработку программного обеспечения часто сравнивают с работой на заводе, пытаясь убрать мистический шарм и стремление к Rocket Science. Давайте начнем рассмотрение с этой точки зрения. Ведь заводы создают инженерные изделия, а программное обеспечение также является инженерным продуктом. К тому же, на нашем условном заводе рабочий может изготовить не только деталь, но и станок, который повысит производительность. Если вы когда-нибудь занимались производством, то наверняка сталкивались с ситуацией, когда не хватает необходимой детали. Когда вы пытаетесь массово собрать какой-то продукт, иногда приходится закупать сотни тысяч однотипных компонентов, чтобы изготовить партию всего лишь в 100 штук. Что же было придумано в инженерном мире для решения подобных проблем? Разработали стандарты, такие как ГОСТ, ISO, DIN и другие.

Разные стандарты металлических изделий по DIN и ISO

С их помощью можно создавать новые изделия, используя готовые блоки, вместо того чтобы искать необходимые компоненты на рынках или у мастеров. Стандартные детали обеспечивают воспроизводимость и повторяемость процесса. Итак, в идеальном мире результат работы устройства можно предсказать, если оно собрано из стандартных деталей с определенными характеристиками. Конечно, иногда могут встречаться дефектные компоненты, но, к счастью, мы привыкли проводить тесты для обнаружения и исправления таких проблем.

В мире разработки программного обеспечения существуют библиотеки, которые можно было бы считать стандартом. Однако есть одно “но” — библиотеки изменяются со временем. Представьте, что каждый год винты M6, используемые вами для сборки оборудования, меняются, и вам приходится адаптировать своё оборудование под эти изменения. Конечно, есть принципы семантического версионирования, и можно остаться на старой версии, но технический долг будет накапливаться со временем. Облачные сервисы могут запрещать использование устаревшего ПО и вынуждать к обновлениям. Другие компоненты могут стать зависимыми от новых версий существующих компонентов. В конечном итоге, ваша программа может перестать собираться по имеющемуся рецепту.

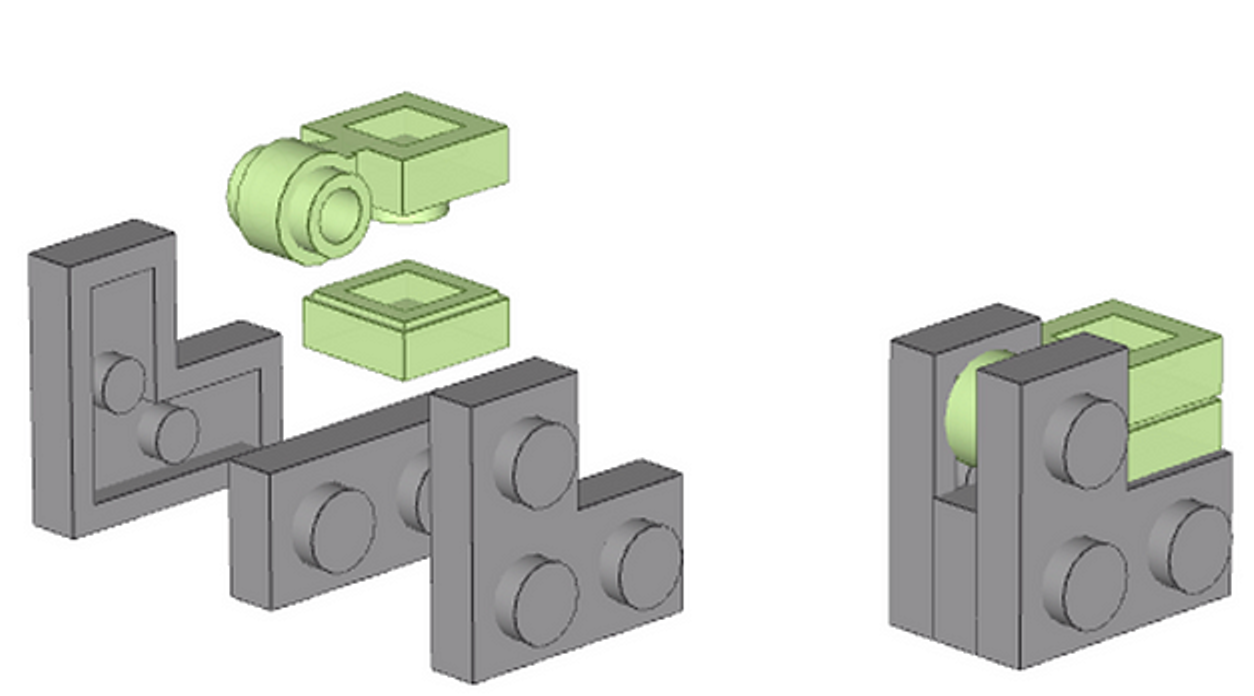

Получается, что разработка программного обеспечения напоминает конструктор LEGO, в котором много деталей, и наша задача — собрать из них работающую систему. При этом важно обеспечить воспроизводимость, то есть результат должен успешно собираться множество раз, даже в самые неожиданные моменты. LEGO — действительно отличный пример. Почему? Потому что детали конструктора совместимы друг с другом благодаря единому интерфейсу, который они разделяют.

Кубики можно соединять совершенно разным образом, но у них один и тот же интерфейс (источник)

Интерфейс кубика LEGO представляет собой цилиндрические выступы и соответствующие разъемы, которые позволяют соединять кубики друг с другом. Благодаря единым интерфейсам, мы можем собирать различные конструкции из кубиков, что является невероятно удобным. Ограничения возникают лишь из-за габаритных размеров деталей. Конечно, если мы хотим создать что-то конкретное, нам нужно знать о кубиках больше, чем просто о том, что они соединяются между собой.

Интерфейсы

Перенеся аналогию с LEGO в мир информационных технологий, мы обнаруживаем, что интерфейсы могут значительно упростить нашу работу. Мы можем “спрятать” детали за интерфейсом, который позволяет нам узнать о них только необходимую информацию и использовать их именно так, как нам нужно.

Интерфейс определяет процесс обмена информацией и возможные сценарии использования какого-либо объекта.

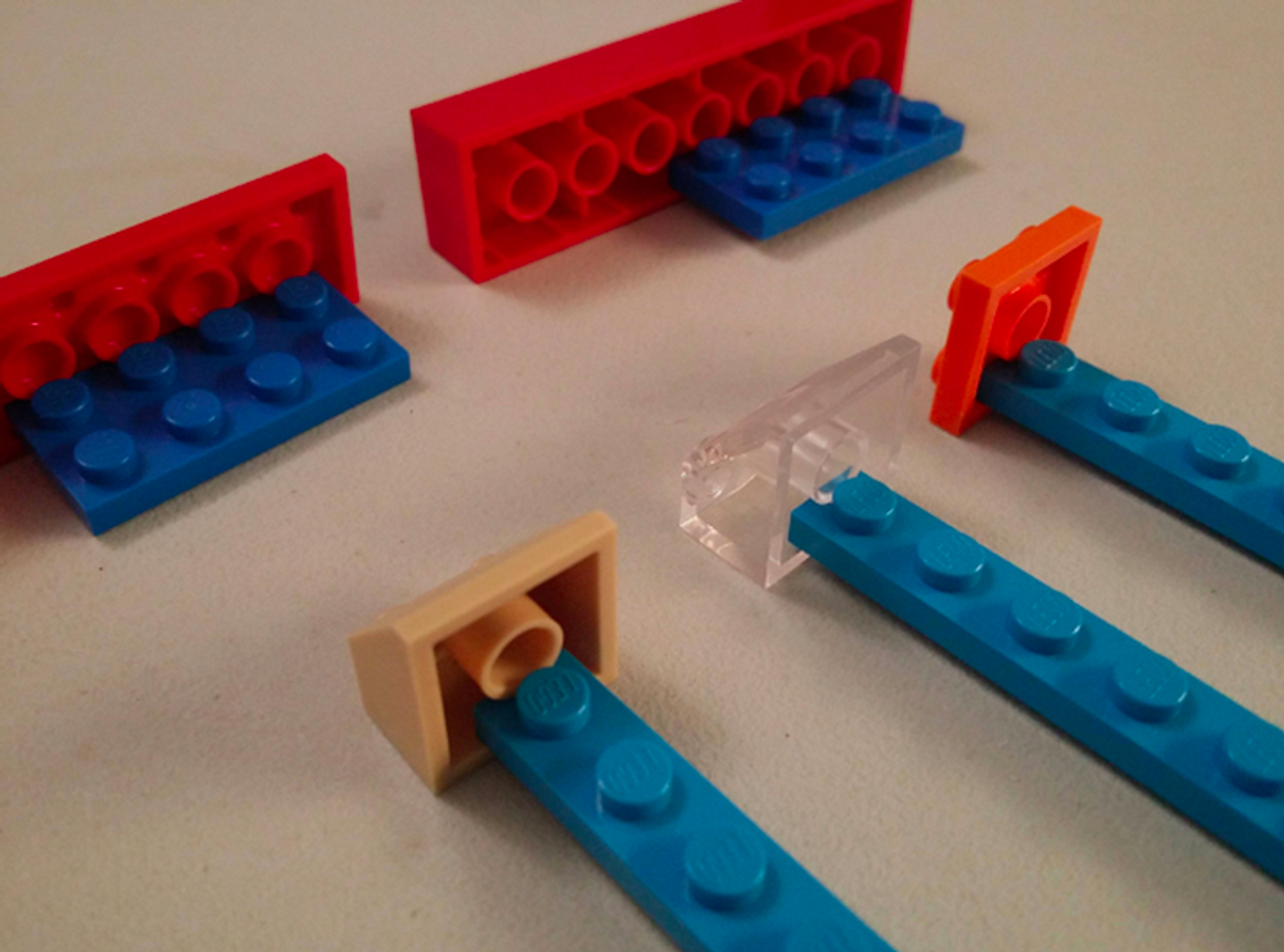

Давайте рассмотрим принципы SOLID, которые часто обсуждаются на собеседованиях, а именно две составляющие: ID, то есть Инверсия зависимостей (Dependency Inversion) и Сегрегация интерфейсов (Interface Segregation). Эти принципы позволяют эффективно управлять сложностью системы, извлекать только необходимые компоненты в конкретном случае и не привязываться к определенной реализации.

Важно помнить, что надо стремиться правильно использовать интерфейсы (источник)

Таким образом, мы можем менять внутренние составляющие системы, не затрагивая внешний интерфейс, и просто извлекать из них нужное. Возможность изменять даже саму реализацию на другую без влияния на остальные части системы обеспечивает гибкость и упрощает разработку и поддержку программного обеспечения.

Интерфейсы действительно присутствуют повсюду в нашей работе. API — это интерфейс, конфигурация — тоже интерфейс. Любой модуль, явным или неявным образом, обладает своим интерфейсом. Когда мы используем модификатор доступа public в некоторых языках программирования, мы также формируем интерфейс.

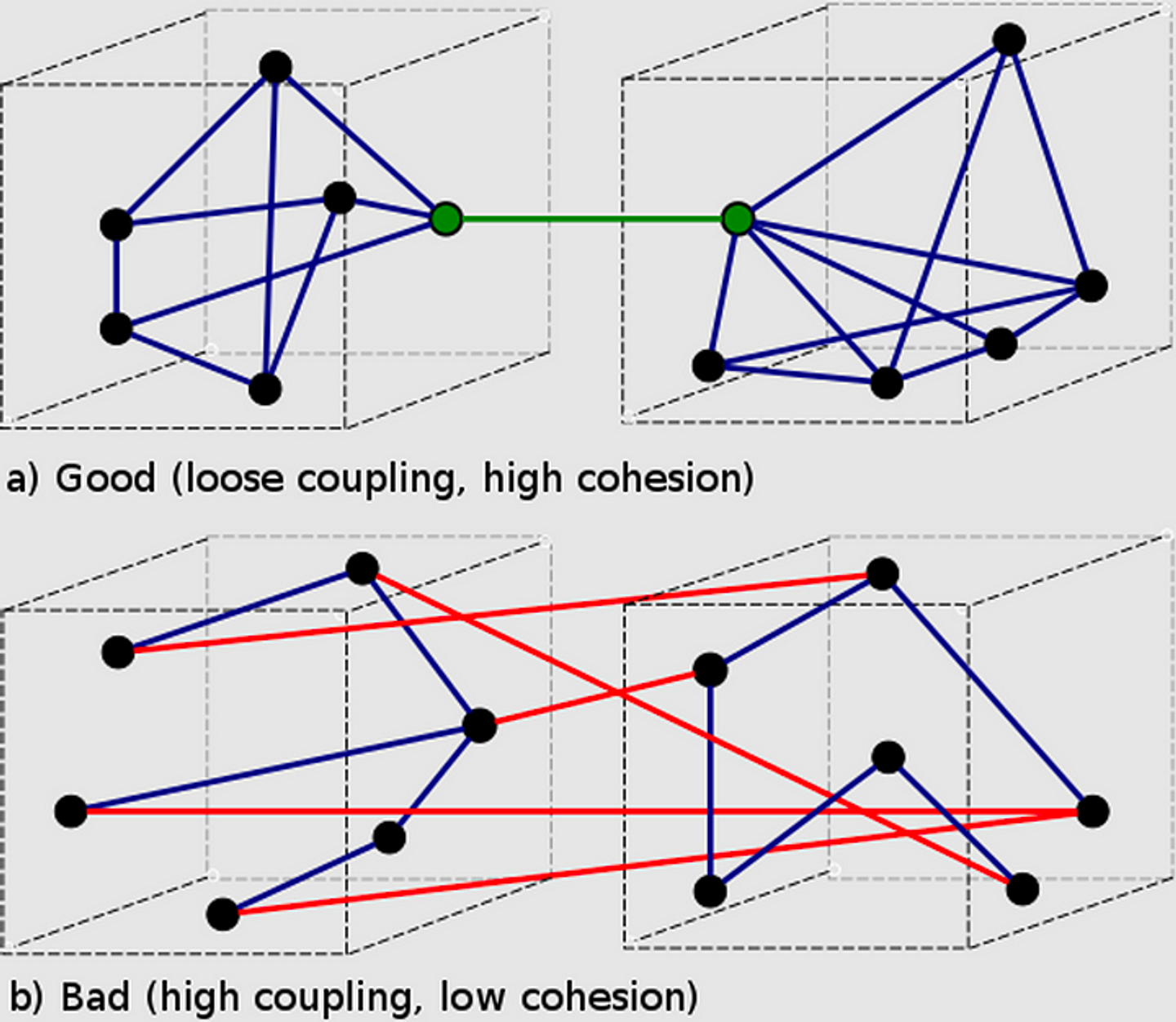

Если мы правильно используем интерфейсы, то граф зависимостей программы становится плоским и разделяется на отдельные части с минимальным количеством связей. Этот процесс называется decoupling.

Decoupling по мнению Википедии

Проблемы

Но надо помнить, что мы живём в сложном мире, сложностью которого хотим управлять. Этот мир не обещает нам, что будет просто. Поэтому есть проблемы.

Домены значений

Первая из них — отсутствие возможности описывать домены значений в интерфейсах. Домен — это область допустимых значений, сочетающаяся с определенным типом данных. В контексте интерфейсов, это ограничивает возможности точного определения допустимых значений для входных и выходных данных, что может привести к ошибкам или непредвиденным последствиям.

Действительно, с развитием языков программирования они стали достаточно умными для определения и проверки типов данных, что может происходить как на этапе компиляции, так и во время выполнения программы. В ассемблере же типов данных не было, и работа велась с памятью, содержащей информацию, которую можно было преобразовывать любым способом.

Концепция типов данных не является врожденной для разработки программного обеспечения, и действительно можно обойтись без неё. Однако на практике использование типов данных существенно упрощает процесс разработки и сопровождения кода, так как позволяет контролировать корректность данных, передаваемых между функциями и модулями, и снижает вероятность возникновения ошибок из-за несоответствия типов.

Действительно, многие протоколы обмена данными и форматы файлов не предусматривают строгой типизации. В CSV, например, отсутствуют типы данных, что может привести к ситуациям, когда программа, такая как Excel, ошибочно преобразует числа в даты или наоборот. В протоколе HTTP типы данных также не определены явно, и часто используется JSON для передачи данных между клиентом и сервером.

Даже типизированные языки программирования не обеспечивают достаточную выразительность. Например, при определении переменной типа int, может быть неясно, получим ли мы int64 или int32. Или где-то сказано, что мы принимаем numeric, который может быть и дробным. Это может вызвать проблемы с преобразованием типов, как показано в наглядных роликах на эту тему.

Также ограничены возможности декларативного описания контрактов в языках программирования. Часто разработчики должны прибегать к добавлению проверок и валидации данных на уровне кода, чтобы обеспечить корректность передаваемой информации и соблюдение контрактов между компонентами системы. Но это остаётся неявной составляющей контракта интерфейса.

Использование чужих интерфейсов

Вторая проблема заключается в том, что на многих языках программирования сложно интегрировать различные компоненты, даже если их интерфейсы открыты. Проблемы могут возникнуть при попытке заменить один объект на другой, поскольку у него уже есть свой интерфейс. В таких случаях, чужие объекты надо закрывать интерфейсом, который определяем мы сами.

Хотя это может показаться усложнением, на самом деле подход с проксированием интерфейсов значительно упрощает процесс интеграции. В современных языках программирования интерфейсы обычно описываются в месте применения, что позволяет запросить только ту сложность, которая действительно необходима. Это верно не только для императивных, но и для декларативных языков.

В декларативных подходах мы также можем эффективно управлять сложностью, скрывая ненужные детали. Примерами таких инструментов являются Helm и Terraform, которые позволяют абстрагироваться от множества параметров, оставляя только самые важные и нужные для конкретного случая. Это способствует упрощению разработки и улучшению поддержки программного обеспечения.

Ограниченность выразительных средств

Третья проблема заключается в ограниченности выразительных средств для описания интерфейсов. Я уже говорил про отсутствие контрактов, которые бы проверяли принадлежность к сложным доменам. Рассмотрим пример с конфигурацией. Действительно, есть такие инструменты как protobuf, но если мы хотим описать конфигурацию, выбор инструментов оказывается ограниченным. Пусть есть YAML, TOML, JSON, но они потребуют дополнительных затрат сил на фиксирование домена значений. Проект конфигов на протобафе кажется мёртвым (https://docs.protoconf.sh/), но возможно есть и другие варианты.

Конфигурация и её хранение — это действительно сложная тема. Иногда требуется менять параметры в реальном времени, иметь центральное место для хранения конфигураций, а также предоставлять возможность отдельным разработчикам хранить локальные конфиги на своих компьютерах.

Однако, это открывает возможности для разработки новых инструментов и подходов, которые могут решить подобные проблемы. Создание такого проекта может стать успешным пет-проектом для разработчиков, ищущих идеи для своих новых начинаний. Если вам интересно этим заняться, не стесняйтесь и дерзайте — возможно, вы найдете решение, которое востребовано в IT-сообществе.

Неявные интерфейсы

Итак, последняя проблема заключается в том, что мы часто используем интерфейсы неявно. Набор инструкций процессора и протокол TCP/IP — это тоже интерфейсы. Мы скрываем их за множеством абстракций, однако, как известно, любая нетривиальная абстракция протекает. В результате мы сталкиваемся с проблемами, связанными с этими скрытыми интерфейсами, будь то кэш-промахи или латенси между дата-центрами.

В таких случаях у нас есть два подхода: либо явно описать проблему, добавляя переменные, которые учитывают специфику скрытых интерфейсов, либо изменить то, что скрыто за интерфейсом. Оба подхода имеют свои преимущества. Явное описание проблемы позволяет нам учитывать особенности реализации, а изменение скрытых интерфейсов дает возможность модифицировать систему, когда нам это действительно необходимо.

Заключение

Итак. Интерфейсы:

- Помогают управлять сложность

- Позволяют снизить уровень зацепленности (coupling)

- Позволяют скрыть даже плохой код внутри коробочки и не обращаться к нему, пока не будет реальной необходимости

Проблемы:

- Проверка принадлежности к домену значения

- Необходимость оборачивания чужих интерфейсов, чтобы избежать проблем с совместимостью

- Ограниченность в выразительных средставах

- Наличие скрытых интерфейсов из-за большого количества уровней абстракции.